The saying ‘a land without a people for a people without a land’ is probably the most well-known expression associated with the Zionist movement. As such, it is probably also the one statement anti-Zionist activists work most tirelessly and tediously to twist and refute. In this article we will take a look at the origin of the expression, how it is said in Hebrew, what it actually means, how an unfortunate choice of words can play right into the hands of bad-faith actors, and what can be done about it.

The Origin of “a land without a people…”

Believe it or not, the phrase ‘a land without a people for a people without a land’ or ‘for a people without a land, a land without a people’ as it was sometimes said, is not the intellectual property of the Zionist movement. In fact, its origin isn’t even Jewish – it was coined by Christian writers who for their own reasons, promoted the idea of Israel’s restoration and Jews returning to their homeland.

The earliest recorded use of this phrase is owed to a clergyman of the Scottish Church named Alexander Keith. In 1843 he published a book titled ‘The Land of Israel According to the Covenant with Abraham, with Isaac, and with Jacob’, and in it he wrote the following about the Jews:

“a people without a country; even as their own land, as subsequently to be shown, is in a great measure a country without a people”.

The more familiar wording ‘a land without a people and a people without a land’ appeared one year later, in a review of the book in The United Secession Magazine. It is worth noting that Alexander Keith wrote on the matter from first-hand experience as he journeyed twice to the Holy Land. The first time was in 1839 as part of a church mission, and the second time was in 1844 with his son who also documented the journey visually.

There are more instances of the phrase in the writing of Christian restorationists and other prominent figures. The first instance of the phrase in the context of Zionism is attributed to Israel Zangwill who in 1901 wrote in The New Liberal Review that “Palestine is a country without a people; the Jews are a people without a country”. Zangwill was simply echoing a phrase he probably read somewhere, and he did so in his mother tongue of English, but it’s worth seeing how it was later translated into Hebrew.

“A land without a people…” in Hebrew

The English word ‘people’ has two very common Hebrew equivalents. The correct way to translate it totally depends on the context and grammar.

People as simple plural

When it simply refers to several human individuals, the word ‘people’ is most commonly translated to אֲנָשִׁים (anashim). Sometimes it gets a little tricky, because technically speaking, as the plural of the word אִישׁ (ish) which means man, the word אנשים may also mean just men. However, to refer strictly to men we have the word גְּבָרִים (gvarim) – the plural of גֶּבֶר (gever), which is another common way to say ‘man’ in Hebrew. For instance, the way to say in Hebrew ‘I saw five people, three men and two women’ is:

ראיתי חמישה אנשים, שלושה גברים ושתי נשים

| Meaning | Pronunciation | Hebrew |

|---|---|---|

| I saw | ra’iti | רָאִיתִי |

| five (masc.) | chamisha | חֲמִישָּׁה |

| people | anashim | אֲנָשִׁים |

| three (masc.) | shlosha | שְׁלוֹשָׁה |

| men | gvarim | גְּבָרִים |

| and two (fem.) | u-shtei | וּשְׁתֵּי |

| women | nashim | נָשִׁים |

People as a single body

When the word ‘people’ refers to a people in the ethnic sense, its corresponding Hebrew word and most correct translation is the word עַם (am). You may know it from the common Jewish expression עַם יִשְׂרָאֵל חַי (am yisrael chai) – the People of Israel lives. Therefore, the phrase ‘a land without a people for a people without a land’ in Hebrew is:

אֶרֶץ לְלֹא עַם, לְעַם לְלֹא אֶרֶץ

| Meaning | Pronunciation | Heberw |

|---|---|---|

| land, earth, country, state (fem.) | erets | אֶרֶץ |

| without | lelo | לְלֹא |

| a people (masc.) | am | עַם |

| to, for | le | לְ |

I find the Hebrew version of ‘a land without people for a people without a land’ much better than its English origin, and not just because it’s in Hebrew. The reason I like it better is the fact that the Hebrew word עַם (am) does a far better job than the English word ‘people’ when it comes to intentions – both in the sense of the intended meaning, and in preventing people with bad intentions from twisting and manipulating the meaning behind it on purpose.

Indefinite article in a definitive role

The phrase ‘a land without a people for a people without a land’ doesn’t mean that the area known as Palestine was empty of people. It simply means that the people who lived there were not a people in the ethnic or national sense of the word. They didn’t share a collective identity or memory, and that the specific strip of land on which they lived certainly didn’t play any part in their collective ethos or shared history. The reason I know this is that they still have neither of those. Don’t believe me? Just see what Palestinians have to say when asked to name a prominent figure in Palestinian history:

They virtually can’t name anyone before the times of Yasser Arafat (who was born and raised in Egypt by the way). And when they do name figures from Ancient History, they are not Palestinians – Saladin was Kurdish and ruled over Syria and Egypt, and Jesus as we all know was a Jew who lived under the rule of the Roman Empire.

If you think that’s bad, just take a look at more similar videos from the excellent channel of The Ask Project confronting Palestinians with their history. Here’s another one which asks the question ‘When was Palestine Established?’

For people who were robbed of their most precious thing, they sure are having a hard time describing it. Imagine someone calls the police reporting some criminals had just kidnapped his grandma right in front of them, but when asked about her age, description, medical condition, what clothes she was wearing, money and other valuables she may have been carrying, and then he or she has nothing concrete to say. Wouldn’t that be weird?

By the way, it is very important to remember that both the Christian writers who coined the expression and the Zionist movement who adopted it, knew the land wasn’t empty and completely acknowledged the existence of other people in it. In fact, it is thanks to the Christians who visited the land and documented what they saw that we know the nature and the demographics of that existence, and just how scattered and scarce it was. Plus, if the Zionist movement had denied that reality as it was reported in their journals and other published materials, the whole enterprise would have undoubtedly failed.

The Nation Alteration and Revelation

I honestly think that the Zionist movement would have saved itself a lot of trouble if instead of simply adopting ‘a land without a people for a people without a land’, they would have gone with ‘a land without a nation for a nation without a land’. Changing ‘people’ to ‘nation’ not only has a better impact as it hits the nail exactly on the head, but it also preemptively sidesteps the semantic minefield of the word ‘people’.

It is no secret that once you focus the discussion on the concept of nation, the Palestinian narrative crumbles. The Arab world knows this, and that is exactly why they insisted on changing the definition of refugee specifically for Palestinian Arabs after the 1948 war with Israel. The modern Palestinian ethos is essentially an appropriation of the Jewish ethos in every aspect – from ancient history, religion, and holy sites, all the way to catastrophe, exile, and restoration.

The only problem is you cannot rebuild what never existed in the first place, and this is all revealed once you ask Palestinians to define their national identity more concretely. And the best way to do that is to incorporate the word ‘nation’ in the discourse. Starting with ‘a land without a nation for a nation without a land’.

Amicable Ambiguity

Speaking of the ambiguous nature of the Palestinian narrative and national identity, it is interesting to note that for some vague reason, the Hebrew word for people or nation עַם (am) is related to the Hebrew noun עֲמִימוּת (amimut) which means vagueness or ambiguity, and to the Hebrew verb עִמְעֵם (im’em) which mean to dim, to muffle or to obscure. Maybe it’s because once something is spread among the people, be it a physical object or an idea, it is bound to go through some changes, or wear and tear, until it is more of an echo of what it was originally. Here’s a really good example of that in real life:

The word עַם (am) is also very similar to the preposition עִם (im) which means ‘with’ or ‘among’, but in this case the connection is more obvious. The same preposition in Arabic is مع (ma’a) which spelled with the same two letters as in Hebrew, only backwards. In ancient Hebrew the word עַם may have meant uncle, and more specifically father’s brother. This is still the case with the Arabic word عم (am) which is how you say uncle today.

The Hebrew word for nation is אֻמָּה (uma) and it also relates to family on some level as it stems from the same shoresh as the word אֵם (em) which means mother. In English and other European languages, the concept of nation is also related to mother through the root NAT which means birth.

Now that I think about it, there is also a better way to say ‘a land without a people for a people without a land’ in Hebrew, and that is:

אדמה ללא אומה לאומה ללא אדמה

| Meaning | Pronunciation | Heberw |

|---|---|---|

| soil, land | adama | אֲדָמָה |

| without | lelo | לְלֹא |

| nation | uma | אוּמָּה |

| to, for | le | לְ |

This version even rhymes, so it must be true!

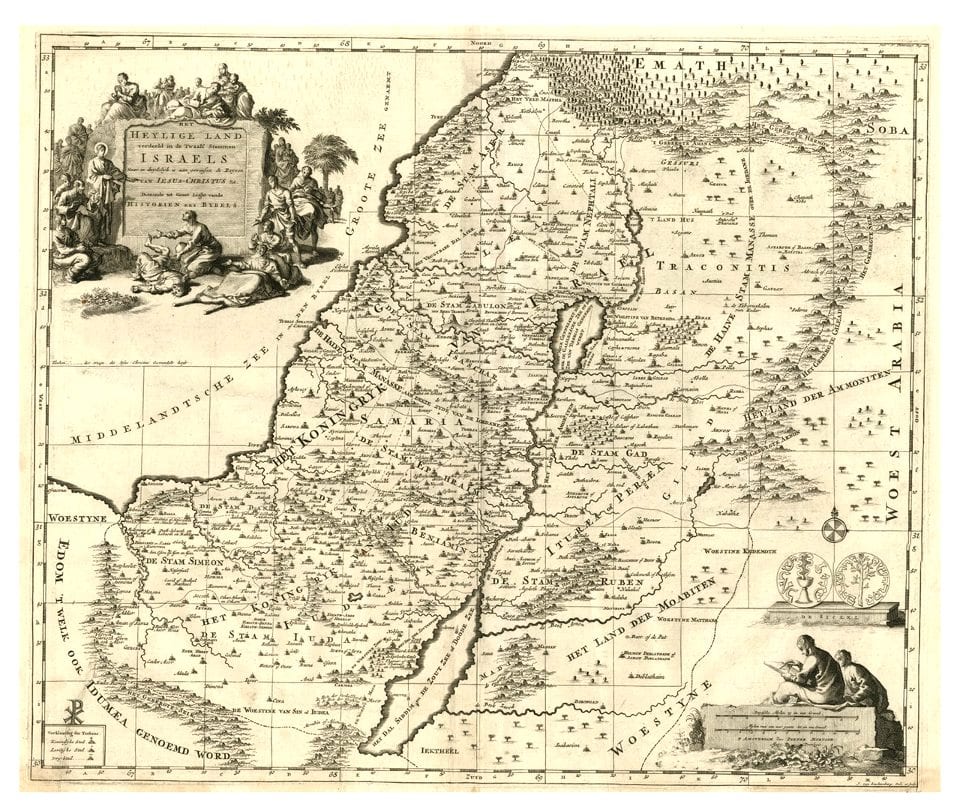

Cover photo explained

The cover photo is a piece of cloth with the Hebrew word יִזְכּוֹר (yizkor) written on it. It is a verb which means ‘will remember’ or ‘shall remember’ for the third person masculine singular. This word actually appears right before the word עַם (people) in יזכור עם ישראל (Yizkor Am Yisrael) – an expression that states the people of Israel shall remember and opens the commemorative prayer said on Israel’s Memorial Day to honor the all the fallen soldiers and victims of terrorism. I thought it would be fitting for an article that revolves around collective memory.

Stay in Touch!

Get the next post from Hebrew Monk directly to you inbox!

Don't like emails? Subscribe to Heberw Monk's Telegram Channel instead.