Abortions is the only topic on everyone’s lips these days it seems. Not only in the US, but also in Israel and many other places, at least according to my social media feeds. Last week, in a giant act of virtue signaling the Israeli Ministry of Health, even announced they will ease abortion regulations in response to Roe vs Wade overturn.

Growing up in a secular and fairly liberal Israeli household, like most of my peers, up until not so long ago I was on the pro-choice side of the abortion isle. I have never really given it much thought, I just “knew” this was the right thing to do – or rather to be.

However lately, I have been thinking more and more about this issue and about the Hebrew word for fetus in particular, and I think we need a clean-up in the abortion isle, because the water holding the pro-choice argument just broke for me.

Fetus in Hebrew

The most common way to say fetus or embryo in Hebrew is the word עֻבָּר (ubar). The shoresh of this word is ע-ב-ר (Ayn-Bet-Resh), which can also be found in the word Hebrew itself (עִבְרִית). The basic meaning of this root is to pass or to cross, and it also largely corresponds with the Latin prefix ‘trans’.

For instance, the Hebrew verb הֶעֱבִיר (he’evir) is a common translation for both the verbs ‘transfer’ and ‘transport’ in English. Also, a transit camp is מַעְבָּרָה (ma’abara), ‘transition period’ in Hebrew is תְּקוּפַת מַעֲבָר (tqufat ma’avar) and a transit flight is טִיסַת מַעֲבָר (tisat ma’avar).

There are two ways to explain the presence of the shoresh ע-ב-ר (Ayn-Bet-Resh) in the word עֻבָּר (ubar – fetus). The first and most obvious one is the fact that a fetus is a result of a transference – in order for one to be created, a man must transfer something from himself into the female body. This logic can also be seen in the verb ‘to impregnate’ in Hebrew which is עִבֵּר (i’ber), and the term impregnated woman which in Hebrew is said to be מְעוּבֶּרֶת (me’uberet).

The second option is to view the fetus as a being which exists in a process of transitioning or that transitioning is its main purpose. If we take this more fetus-centric approach, we can also explain the verb עִבֵּר (i’ber – impregnate) as the act of creating an embryo inside a woman’s body (by transference).

I honestly don’t know which explanation is the correct one, and it is more than likely there is some truth to both of them. But either way, you simply cannot deny the connection between the word עֻבָּר (u’bar – fetus / embryo) and the concepts of passing, crossing, and transitioning that the shorsh ע-ב-ר (Ayn-Bet-Resh) represents.

To me this was a huge revelation. All of a sudden, a fetus seems far less vague and distant a concept to me. It is a being or an entity which is going through something and is waiting to cross over to our side.

Abortions and other “Transitory” Rights

This revelation has also made me think about other hot political issues, which are also directly linked to the basic meaning of the shoresh ע-ב-ר (Ayn-Bet-Resh) – Trans Rights and Immigration. Ever since I have noticed this etymological connection, I simply cannot see how someone can claim trans rights are human rights, yet casually dismiss those rights for a human who is actually going through the natural process of transitioning.

I also cannot see how someone might claim some individuals should have the right to cross a border and that they must be well received and treated fairly because they have no other choice, yet also support the preemptive killing of other individual who really don’t have a choice when it comes to their inevitable need to cross over and enter the world.

The Golem Effect

I didn’t know this before I started writing this article, but apparently in Biblical Hebrew there is another way to refer to a fetus, more specifically – a fetus which hasn’t formed the shape of limbs. The word is גֹּלֶם (Golem), which most people know from Jewish folklore as an undead humanoid creature created from clay or mud.

The word גֹּלֶם appears only once in the Bible, in the Book of Psalms (139-17) in the sense of raw form. In later interpretations of the Bible, it is also used to refer to the body of Man created from the earth before God breathe life into him.

One of the other ancient meanings of the shoresh ג-ל-מ/ם (Gimel-Lamed-Mem) is to fold over. It is regarded as a derivative of the primal roots ג-ל (Gimel-Lemed) which refers to waves, stacks, and piles, and as a relative of the root ג-ל-ל (Gimel-Lamed-Lamed) which refers to rolls. I discussed them briefly towards the end of the post ‘Buried in the Sand – Hebrew as a language of desert people.

In Modern Hebrew the shoresh ג-ל-מ/ם preserved the meaning of raw, crude, or unrefined – especially in nouns and adjectives. For instance, crude oil in Hebrew is called נֶפְט גּוֹלְמִי (neft golmi) and raw material is known as חֹמֶר גֶּלֶם (chomer gelem). When it comes to verbs, it mostly expresses the meaning of ‘to embody’ or ‘to have the potential to be or become’, like in the verb גִּלֵּם (gilem), the verb הִתְגַּלֵּם (hitgalem) and the more passive form גָּלוּם (galum).

A Butterfly in the Rough

The most common meaning of the word גֹּלֶם in Modern Hebrew is a cocoon, and this new connection to fetuses also made me see abortions in a new light.

The main question that popped into my head was this:

If you saw a child squashing a cocoon of a butterfly in his or her hands, would you be able to tell them they didn’t just kill a butterfly? Would you even want to start making this sort of rationalization?

For me the answer is no, and I would not want to live in a society that is okay with squashing cocoons on the technicality they are not yet butterflies. That is one loophole I really don’t want to fall into.

Now I know this is neither a fair comparison nor a perfect analogy. In the case of abortions, the “shell” of the cocoon is a sentient being, perfectly capable of making a choice to squash whatever is in it. Therefore, since I do believe the right of individuals over their own body triumphs even here, I am fundamentally and ultimately still pro-choice. However I think it should be a well-informed and incredibly honest choice. And the first step towards that kind of honesty is to admit to ourselves we are killing butterflies here.

The Revealing Nature of Language

Our use of language can be very revealing. The way we unconscientiously choose words can tell us a lot about how we really think and what we actually believe. For example, we all believe that once an object, if left alone to its own devices is able and will inevitably transform itself into a different thing, is in fact already that thing – especially after the process has started.

Added on July 26th 2022

I saw the latest Bill Burrs Netflix Special ‘Live at Red Rocks‘ where at the end he also talks about abortions and uses a cake analogy. I swear I didn’t watch it before I wrote this article. Plus, cake and bread are two completely different things 😉

When does bread become bread?

Let say you want to make bread. You start by mixing flour, yeast, salt, oil, and water in a bowl to make dough. Then you need to wait for a while and let it rise. Now if someone came and accidentally spilled coffee or juice all over your dough, you might tell them they ruined your dough, or you might tell them they ruined your bread. The first statement is technically more accurate but the second one is also valid.

However, once the dough is in the oven, if someone came and started messing with the temperature, or accidentally opened the oven’s door too early, the only thing you would say to them is that they are ruining your bread. It doesn’t matter if it happened two minutes before the bread is ready or two seconds after you put it in the oven and closed the door – once it’s in there, it is no longer dough. It’s bread. Why? You can’t eat it yet, but the mere fact the process has started changes everything.

We apply this logic pretty much everywhere. If you step on an oak sprout and break it, you know you killed a tree. It doesn’t have a trunk nor leaves and branches, yet you know it’s a tree. I studied photography when films were still (just barely) in use. If you turned on the regular lights in the dark room while someone was working there, they would scream at you that you were ruining their photos, even though no shapes had yet formed on the paper submerged in chemicals. When you start drawing a circle and somebody bumps into your hand, would you tell them they ruined your circle or your line?

For some reason we don’t apply this logic in the case of abortions. Yet this is exactly why when a pregnant woman has an accident but seems to be fine, the first question on everyone’s mind is “is the baby alright?”. Not “is the fetus alright” and certainly not “Is the clump of cells in her belly alright?”.

This truth also exposes itself in the way we process language and information. If someone told you a young woman died in a car accident, you will undoubtedly get sad upon hearing it. If they added that she was seven months pregnant that would presumably make you sadder, would it not? Why? Because you cannot help but knowing what you know.

The Butterfly by Pavel Friedmann

The last, the very last,

So richly, brightly, dazzlingly yellow.

Perhaps if the sun’s tears would sing

against a white stone…

Such, such a yellow

Is carried lightly ‘way up high.

It went away I’m sure because it wished

to kiss the world goodbye.

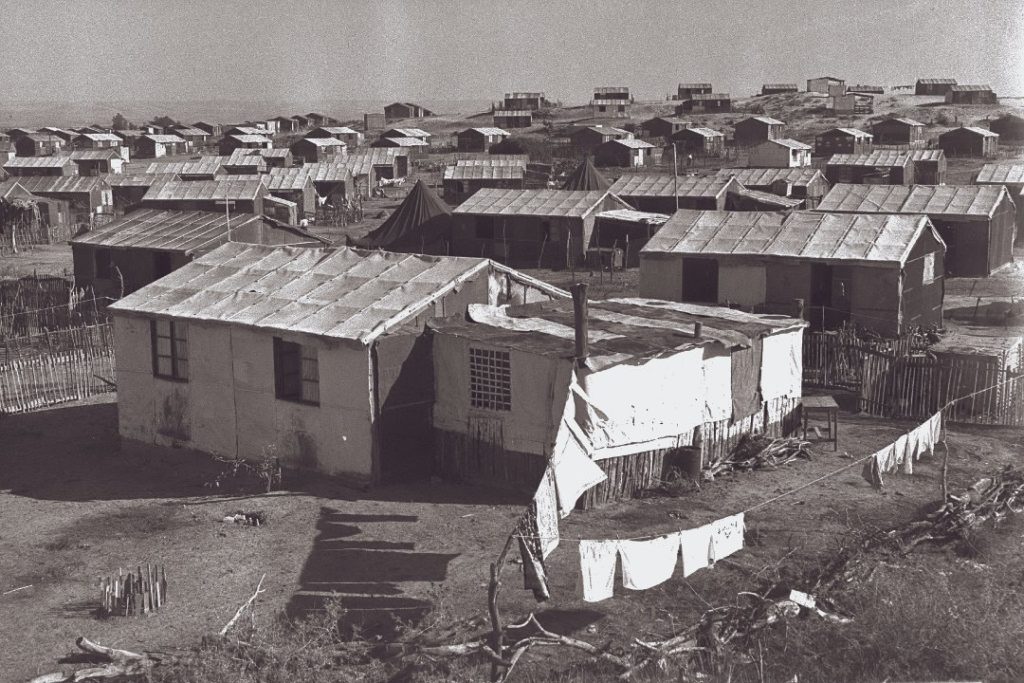

For seven weeks I’ve lived in here,

Penned up inside this ghetto

But I have found my people here.

The dandelions call to me

And the white chestnut candles in the court.

Only I never saw another butterfly.

That butterfly was the last one.

Butterflies don’t live in here,

In the ghetto.

This poem was written by Pavel Friedmann, at Theresienstadt concentration camp on 4 June 1942. On September 29, 1944 he was deported to Auschwitz where he died.

Stay in Touch!

Get the next post from Hebrew Monk directly to you inbox!

Don't like emails? Subscribe to Heberw Monk's Telegram Channel instead.